Feature Interview with George Waters

January 2014

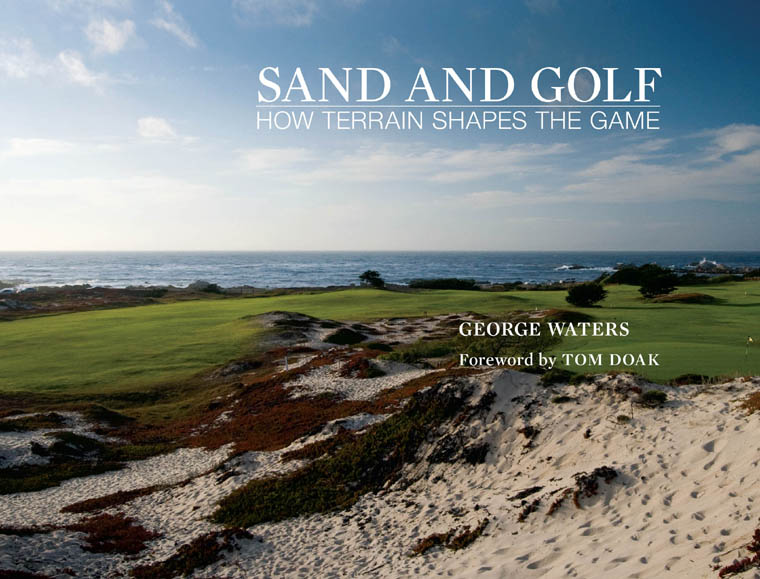

George Waters is an up and coming member of the next generation of golf course architects. Having participated in the design and construction of several of the world’s most significant new courses, in addition to the restoration of some classics, George has gained extensive golf course design and construction experience working on sandy terrain. He holds a Masters Degree in Landscape Architecture from the University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada, where his Masters research focused on golf courses in coastal dunes and included field study of the great links in Great Britain and Ireland. Since then, he has both visited and worked on with leading architects some of the world’s best courses in the United States, Great Britain, Ireland, Continental Europe, and Australia including Barnbougle Dunes, Sebonack, The Renaissance Club at Archerfield, California Golf Club of San Francisco, and Pinehurst No. 2. His new book, Sand and Golf: How Terrain Shapes the Game is a product of those travels and his particular expertise regarding golf courses built on sandy terrain.

1. The title of your just released book Sand and Golf – How Terrain Shapes the Game says it all and yet, no one has ever touched the subject in-depth. What propelled you to do so?

From very early in my career I focused a lot of my attention on sandy terrain. I grew up on Long Island and was aware of the aura surrounding sandy courses like Shinnecock and The National long before I’d ever seen any of them. My first job in golf was on the maintenance staff at St George’s G&CC in my hometown of Setauket, NY. There I began to develop an appreciation for traditional architecture, open approaches, and firm conditions. Not long after that I volunteered on the maintenance staff at Royal Dornoch for a summer and saw for myself the classic links golf that had inspired the famous courses on Long Island. Those early impressions motivated me to seek out opportunities to work with sandy terrain, no matter where in the world that took me. I was also trying to read as much as I could about courses built on sand. I found lots of books about links courses, but there were very few that touched on other types of sandy courses in much depth. It seemed that there was an opportunity to explore the wider world of sandy courses as a whole.

2. As a first time author, how hard was it to get the book published in such a quality manner?

I benefited from a lot of good advice and a fair amount of luck. I knew very little about modern book publishing going into the process and friends like Brad Klein and Paul Daley were very helpful throughout. There are lots of different ways to get a book published these days and I was able to generate a decent amount of interest in the project, I think largely because the photos were very appealing. Also, I made a good decision in working with my own graphic designer to develop a preliminary layout before shopping the book around. That helped people see how the photos were going to relate to the text. I ended up going with Goff Books because they had a lot of experience publishing design books, so they knew how important the visual presentation of the book was going to be. They also had a lot of experience working with designers, so they were comfortable with the idea that I was going to be heavily involved in the process. In addition, they happened to be based in Marin County which is a short drive for me from San Francisco, so I felt like I could always “pop in” if anything needed to be ironed out in person. They turned out to be an ideal choice, and in that regard I was lucky because I didn’t know very much about how to select a publisher. They really put together a beautiful book and I’m sure they made countless good decisions that I’ll never even know about.

3. Please expound on your wonderful statement, ‘Golf on sandy ground requires more than studying a yardage guide – it requires studying the landscape.’

My first real exposure to golf on sandy terrain was during the summer I worked at Dornoch. I spent all morning working on the course and most evenings either caddying or playing. I learned pretty quickly that golf on sandy ground was not like golf on a lush, green, parkland course. The firm, irregular terrain and windy conditions meant there was a lot more to consider on every shot than just distance. I bought a yardage guide before my first round at Dornoch and I’m not sure I ever looked at it again after that. Rather than considering the holes from above, as they are presented in a yardage book, I realized that I needed to be studying what was in front of me. Which way was the terrain sloping? How hard was the wind blowing? Could I use that subtle wrinkle to steer a shot towards the green? Did the approaches seem firm today, or had they been softened by a bit of rain? How thick was the heather to the right of the green? Each shot became a study of the landscape in front of, and around me, and each round brought new information about that landscape that might be of use next time. As I visited more sandy courses I found myself engaged in that same landscape study. When I got back to playing non-sandy courses, including some good ones, I was a bit disappointed that golf had once again become primarily a question of hitting to a yardage.

4. Not all sandy courses are equal. What are the differences of a links versus sandy courses set well into the interior (e.g. Pinehurst, The Sand Hills of Nebraska, Heathland courses, Melbourne’s Sandbelt)?

In my experience it is easier to achieve really good firm and fast conditions on links courses because they generally enjoy a more moderate coastal climate. The natural environment of most links courses lends itself to ideal golf conditions, which isn’t surprising since it is the environment that gave rise to the game in the first place. The more continental climate of places like Nebraska means more extremes of heat and cold. Where cool season grasses prevail, very hot summer weather is going to have an impact on how dry and firm a course can be maintained. Where warm season grasses dominate it can be a challenge to replicate links conditions with grasses that feature coarse leaves and a tangled mat of growth. In addition there is the difficulty of handling winter when the warm season grasses tend to go dormant. Overseeding has been the preferred method for a long time, but that effectively puts an end to firm and fast conditions as lots of water is applied to encourage the newly seeded grass. Things are changing for inland sandy courses, however, as new turf cultivars are developed and new approaches to maintenance are employed in an effort to bring consistently firm and fast conditions to more challenging climates.

5. What are the primary benefits of building in sand from an architect’s perspective?

Tom Doak handles this exact question very well in his Foreword to Sand and Golf so I’ll let him answer: “For a golf course architect, the practical advantages of working in sandy soils are many. You never have to worry about falling behind schedule in construction, because rain percolates quickly through the soil and does not stop you from shaping or finishing the holes. The soil is easier to move and easier to clean up, so you can work with smaller equipment and create more intricate contours. You can use native soil for the greens mix and bunker sand, and you can leave little folds in the ground to add interest in the fairways and greens without worrying about them turning into bird baths. Best of all, as you are shaping the greens, fairway contours, and bunkers, your first draft is the final effort. You do not have to allow for topsoil to be plated over the contours, or allow for a drainage layer under bunkers and greens. What you see is what you get; you can stand in a bunker and see exactly the recovery shot that will have to be played, and dig the bunker slightly deeper or fill it in a bit to get the shot values you want.”

6. How did your own ‘in the dirt’ experiences influence the book’s composition?

There is a certain “how-to” aspect to the book. That is a product of my experience in the field. I talk a lot about the unique features of courses built on sand, and what makes many of those features special is that they are nearly impossible to replicate elsewhere. That awareness came from trying to recreate those features myself and very seldom succeeding. This gave birth to sections like “The Washboard Effect”, “The Sphere of Influence”, and “The Natural”. All are concepts I tried to implement on sites with heavier soils and was never able to achieve the same success I had on sandy terrain.

Waters’ first project with Tom Doak was Barnbougle Dunes, where he saw for himself the architectural advantages of working with sand.

I had also seen first-hand the difference in the construction process between sandy sites and those with heavier types of soil. It was easy to preserve interesting contours and features on sandy ground, and the great results achieved when carving bunkers directly into the sandy soil. I had also seen how much was lost in processes like topsoil stripping, USGA green construction, and massive drainage installation; all of which are common when working with heavier soils. This gave me an understanding as to why many sandy courses seem to have an extra layer of detail, and those details formed much of the basis for this book.

Not to mention, building a golf course isn’t something you do alone. Spending a lot of time in the field gave me the chance to discuss countless details of the sandy courses I was building and playing with some of the best minds in the business. Those conversations certainly helped shape the book. My discussion of recovery play around the 16th green at North Berwick in the section “Short Grass in all the Right Places” is a direct product of debating with the guys from Renaissance Golf about the best way to play to that green after missing your approach and ending up on the 17th tee. I would not have thought as much about concepts like that if I hadn’t spent so much time discussing them, either on-site or after work.

7. What are the primary benefits of building in sand from an owner’s perspective?

Building in sand gives an owner a serious leg up because of the design and maintenance possibilities offered by sandy terrain. Sandy soils can make a good site great, but they can also allow a relatively modest site to produce a first rate golf course. Courses like Pinehurst Number 2 and Carnoustie occupy very gentle topography and don’t offer much in the way of views, yet they are widely heralded as among the best in the world, have played host to numerous great Championships, and both welcome throngs of visitors each year. Sandy terrain is what allows these courses to succeed beyond the limits of their topography, and the same is possible on sandy sites elsewhere.

Not only do sandy sites offer the firm and fast conditions and architectural possibilities that are almost impossible to replicate on other types of terrain, they are more economical to build and cheaper to maintain. They can provide great golf in the face of tight budgets, water restrictions, and many of the other challenges that face the golf industry today. As the world places an increasing emphasis on environmental responsibility, courses built on sand are well placed to take a leadership role, putting their owners at the forefront.

8. What are the primary benefits of playing a course built on sand from a player’s perspective?

To me the principal advantage is freedom. There is no right way to play a sandy course. Many different playing styles can be successful if they are carefully planned and executed. I am a shorter hitter with a naturally low ball flight and a fairly keen eye for detail, so it should come as no surprise that I felt immediately at home golfing on sandy ground. I found that I had enjoyable matches with players who could hit the ball farther and higher than I could, so long as I played within myself and really thought my way around the course. In addition, because courses built on sand are designed and conditioned to accommodate a wide range of playing styles, they are enjoyable to play for a lifetime. They are welcoming to a junior player and they allow a longtime player to use skill and knowledge to make up for brute strength. Courses built on sand are better equipped to challenge each player in different and interesting ways, and to me that’s what golf is all about.

9. Please expand on your term ‘washboard effect.’

The washboard effect refers to the endless small-scale undulations found in many of the best sandy fairways. When fairway undulations become too large, every shot ends up in the valleys between the humps. The tiny wrinkles in a washboard fairway allow the ball to come to rest on any angle, each presenting its own challenge. Stance and lie influence your strategy on every shot, and sandy courses make the most of this subtle challenge. Your entire plan for a hole can be altered by finding your ball on the downslope of a tiny washboard wrinkle. Muirfield, North Berwick, and the Old Course each boast a wealth of this topography, and indeed each of these courses depends on the washboard effect to provide strategy and interest on their otherwise gentle sites.

Sadly, washboard contours are very difficult to replicate away from sandy terrain. Part of the problem is that small wrinkles don’t stand up well to the construction processes that are often necessary when dealing with heavier soils, such as topsoil stripping and large scale fairway grading. Sandy sites generally require less work with smaller equipment, so it is much easier to preserve small wrinkles and incorporate them into the design. Another problem is that most soils lack the drainage characteristics required to accommodate an endless sea of wrinkles. If you tried to build a washboard fairway in heavy clay the many dips and hollows would often be sopping wet. That is why the subtle wrinkles that do exist on sites with heavier soils are typically graded away, allowing water to gather in a few large basins or sheet entirely off the hole, effectively ending any hope for a washboard effect.

10. How have advances in golf course maintenance helped sandy courses to shine?

Advances in golf course maintenance have helped sandy courses to improve and shine throughout golf history. Developments in mowing technology and discovering the beneficial effects of top-dressing helped Old Tom Morris convert the greens on the Old Course from haphazard plant materials to finely mown turf. Turfgrass advances allowed Donald Ross to convert the sand greens of Pinehurst Number 2 into the famous surfaces we know today. In my own lifetime I have seen several major advances in agronomy that have benefited sandy courses. New strains of Bermuda grass that feature a much finer leaf allow courses like Streamsong, in central Florida, to play more like a links than any warm season turf I’d seen in the past. Experimentation with herbicide resistant fescues might help preserve the open and playable native areas I talk about in my book, or help restore those that are overrun by undesirable grasses. There are also a number of sandy courses that are eagerly hoping for the arrival of a means to control poa annua invasion in their greens. This would help them maintain firm and true putting surfaces in what are often poa friendly climates. That may be the next leap in golf course maintenance that significantly benefits courses built on sand.

By the same token, each advance has its consequences. Just because we have a new technology or chemical at our disposal does not mean that we have to use it. Advances in agronomy and golf course maintenance technology helped courses built on sand evolve from rough and rugged pastures to playable and maintainable golf courses, able to handle the growing demand for golf. But as that technology continues to advance we are faced with certain choices. The area of green speeds presents an obvious issue, as we saw recently when alterations were made to the Eden green at St Andrews to accommodate today’s faster green speeds. There was widespread outcry, and justifiably so. Trading extra tilt and contour for faster green speeds is seldom a good bargain. I would hate to think that classic sets of greens are going to be subjected to increasing simplification just to keep up with “advances” in our ability to provide fast greens.

Similar issues are present with advances in irrigation technology. Just because we have the ability to cover every square inch of a property with overlapping coverage doesn’t mean that we necessarily need to. Some sandy courses have certainly lost a bit of character by being too well irrigated. One of the most interesting aspects of the restoration at Pinehurst Number 2 was a return to a simpler irrigation layout, essentially a single row of sprinklers. If areas along the perimeter of that coverage burned out a bit during the season so be it. Finding the balance between what we can do, and what we should do is one of the great challenges in golf course maintenance, on sandy and non-sandy courses alike.